Dominican Republic

Rickard S. Toomey, III, Ph.D.1 and Elizabeth G. Winkler, Ph.D.

1Kartchner Caverns State Park, P.O. Box 1849, Benson, AZ 85602, phone 520-586-4138, fax 520-586-4113, cell 520-508-8762, email rtoomey@pr.state.az.us

Report to the Ministry of Environment, October 29, 2001

In October, 2001, we visited the Dominican Republic to advise the Ministry of Environment on development, operations, conservation, protection, and management issues at Cueva de las Maravillas. During our stay, we worked primarily with Marcos Barinas and Domingo Abreu Collado. This report is a supplement to the extensive discussions we had with them. It does not cover all of the topics that we discussed. In addition, it contains some information that supplements our discussions. Also, many of the comments address issues that the Ministry is already addressing. We include comments on these issues for information.

First, it is important to note that overall we were very impressed with the quality of the planning and implementation which has been undertaken for the protection and development of the cave. We are also impressed with the expertise and concern of the personnel that are in charge of the development and planning. Because of all this, we feel that Cueva de las Maravillas can be developed and managed in a way that protects the cave and its contents (including pictographs). In addition, we feel that it can be exhibited in a manner that will provide an enjoyable and educational visitor experience focusing on both the natural environment and cultural history.

We have organized this report in terms of the issues that accompany the various areas of the development and operation of the cave. Some of the issues span numerous areas; however, we have dealt with these in the area in which they seemed most significant. The areas include:

1. construction, including trail planning and design,

2. potential major cave environmental changes

3. lighting, including potential algae growth

4. clean-up

5. tour and cave operations

6. resources inventory and cave condition monitoring

7. museum operations

1. Construction

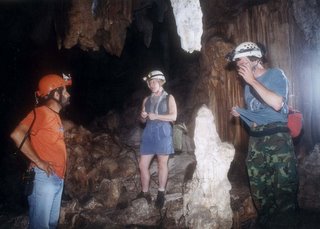

Rickard Toomey y Elyzabeth Winkler discuten con Marcos Barinas, Victor Garcia, Domingo Abreu e Iko Abreu, parte del equipo de habilitación, en la Cueva de las Maravillas.

The most serious conservation issue we observed in construction is the dust that is generated by the jackhammers. There are several ways to mitigate the quantity of dust that is produced by this work. Some mitigation techniques are already being used. For example, plastic is being used to protect significant speleothems from construction-derived dust. The quantity of plastic should be expanded, especially as construction moves to the pictograph areas. An additional suggestion is to put a plastic tent over the area in which the jackhammered is in use; this will help keep the dust contained in the tented area. Furthermore, holding a wet mop, broom, or brush on the jackhammer bit as it works will catch or wet much of the dust and keep it from getting airborne.

We would also recommend that care be taken in choosing materials for use in the cave. The cave environment is very hard on metal and electrical components due to the high humidity. Metal parts should be stainless steel wherever possible. At Kartchner Caverns we have found that galvanized and chrome-plated steel parts are subject to significant corrosion. We have also found that many substances, such as the insulation on electrical wires, will support the growth of fungus in the cave. For that reason, we suggest that samples of any product that might be used in the cave should be placed in the cave for a period to test whether they support fungus growth.

Trail Planning and Design

The planning and design of trails, as presented to us, seems very good. The use of built-in lint curbs and rope-light trail lighting is well designed. In addition, the use of the integrated trail and curbs allows for easy washing down of the trail with water. Also good is the plan to use sump pumps to catch the water used for washing the trail. Experience at Kartchner Caverns has shown that the runoff water that results from washing the trails is very dirty and contaminated. Removing that water from the cave by pumping it out of sumps protects the cave from this source of lint, nutrients, and exotic chemicals.

Based on experience at Kartchner Caverns, we would recommend that in areas where rope-light is used on only one side of the trail, the main handrail should be on that side as well. Both of those features attract people to the side of the trail they are placed on. So, they can be used to keep people on one side of the trail or another as desired.

During our visit, we discussed non-skid surface treatments for the cement walkways to protect the visitors from slips and falls. These are important, because cave trails are frequently wet and lighting is not necessarily ideal. The most common manner of creating a non-skid surface on cement in surface applications in other types of public areas is to use an epoxy coating on the cement. However, this is not an appropriate method for use in a cave. The epoxies tend to give off a variety of gasses as they cure. These can be harmful to the cave environment and animal inhabitants. An alternative strategy for creating an anti-slip cement surface is to incorporate aluminum oxide (emery) aggregate into the finishing coat of cement. At Kartchner Caverns, we have used a product called Frictex that is produced by Sonneborne, a division of ChemRex. This is dry-troweled into the finishing coat of cement after it has begun to set.

Although the Ministry is already committed to a concrete trail at Cueva de las Maravillas, we feel that it is important to note that this is not a universally favored method of cave trail construction although it is common in the United States. In many portions of the world (and in some caves in the United States), reversible construction is preferred for conservation reasons. Should plans for the use of the cave change, the trails could be removed, and the cave would be restored to nearer a pre-development state than would be possible with permanent concrete trails. Some options that have been used in building this kind of trail have included boardwalks (usually of recycled plastic lumber) and trails with laid concrete pavers on a bed of sand. Although we would not recommend changing the plans at Maravillas at this point, it may be worthwhile to consider this method of trail construction for future development in other caves. Doing this in future cave development would have the added advantage of addressing some of the criticism of those not in favor of developing caves by having a lesser impact on the cave's natural environment.

2. Potential Major Cave Environmental Changes

Development of a cave has the potential to cause significant changes in the environment of the cave. The types of changes include changes in airflow, microclimate, biology, and atmospheric composition. The reasons for these changes are many. Development activities often open new entrances or partially or totally close existing entrances. This can change the airflow patterns. Changes to airflow patterns can result in microclimate changes as well. Microclimate can also be directly affected by cave tour operations. Tourists and lights add heat to the cave, and tourists add moisture as well. Tourists also exhale carbon dioxide that can raise the carbon dioxide level in the cave. Changes in temperature, moisture, and carbon dioxide in caves have been shown to significantly impact cave features including pictographs. However, the potential for these changes is highest in small, low energy flux caves with very restricted entrances and airflow.

Cueva de las Maravillas has numerous large entrances that allow large amount of airflow. It appears to be a cave with very high energy fluxes and a potentially highly variable environment. It seems unlikely that tour related activity (at the level presented to us) will significantly impact the cave environment in terms of temperature, moisture, or carbon dioxide level. Nevertheless, we would propose monitoring these parameters to see that unacceptable changes do not occur (these are discussed further in the section on monitoring).We have also made suggestions on lighting and visitation that will reduce the likelihood of significant changes in microclimate.

Development can also significantly affect the biology of the cave in numerous ways. In the case of Cueva de las Maravillas, we are particularly concerned about several potential types of alteration. The cave has a moderate-sized, but apparently diverse, bat population. Significant effort should be placed on not eliminating the bats through development. The current plans, which call for little activity in the main bat roosting areas, are a good start. In addition, lighting and tour operations should always provide for areas to which the bats may retreat. This issue is discussed further in the discussion on lighting. In order to adequately determine whether tour activities are impacting the bat populations, it will first be necessary to better understand the bat populations using the cave. If a study has not been previously performed, we would recommend a detailed analysis to determine which bats are using the cave, their number, and their patterns of use. This study would serve as a baseline for on-going monitoring activities of the bats that will be discussed in the monitoring section. Furthermore, the native cave invertebrate fauna could also be impacted by development. We would recommend some baseline studies of the invertebrates of the cave as well.

Another major biological concern is the potential for the development of exotic flora in the cave (particularly algae, moss, and lichens). We feel that this is probably the most significant environmental threat in the development of this cave. The growth of plants in response to artificial light in the cave (frequently known as lampenfloren in the cave management literature) would threaten the natural beauty and functioning of the cave and would potentially obscure or damage the pictographs. This issue is discussed in detail below in the section on lighting and potential algae growth.

3. Lighting

Lighting is one of the most crucial issues in the development of a cave from both a cave protection and a visitor experience standpoint. The quality of the lighting determines what the visitors see, how well they see it, and how easily and safely they are able to travel through the cave. In terms of cave protection, lighting influences potential temperature and moisture changes in the cave as well as the potential for algae growth.

Based on our discussions, we understand that the Ministry has already committed to several important ideas that will improve the lighting from both an environmental and visitor standpoint. The decision to use rope light to light the trail is a very good one. It allows the visitor to have sufficient lighting for travel, but, at the same time, does not require excessive area lighting that would encourage algae growth.Another important lighting decision is the commitment to use lighting circuits that are as short as possible. That is, the lighting is being designed so that each set of lights may be individually controlled, therefore, each set is only on for as long as necessary. Reducing the time each set of lights is on, reduces both the heat produced and the potential for algae growth.

During our visit, we discussed a variety of specific light placements and ideas. The specifics of these discussions were noted down at the time by Marcos Barinas and Victor García. Therefore, this discussion will focus more on general recommendations for the lighting of the cave rather than detail the specific comments.

In general, we would recommend use of a mixture of fluorescent and incandescent lighting for the cave. Fluorescent lighting is desirable because it produces much less heat than incandescent lighting while producing the same amount of light. Although we are not overly concerned that the temperature of the cave will significantly increase due to the lighting and visitors, we do feel that it would be prudent to limit excess heat input where practical.At a local level, a reduction of heat at the source of the light, will reduce the possible growth of algae. Fluorescent lights can be purchased in a variety of light qualities. Perhaps warmer-hued lights would be most desirable for the caves colors (a number of manufactures make white linear fluorescent that have different color rendering or color temperatures). Fluorescent lights are also useful for creating a general lighting of an area without too much glare. However, fluorescent lights are not very good at spotlighting features or lighting features that are far from the lights. In cases where this is desirable, incandescent spot lights would be the most appropriate. Care should be taken to place the spotlights in a position so that they do not over-light nearby rocks and create algae.

It is important to resist the temptation to over-light the cave. The brightness of the lighting needs to be enough for the visitors to see the features, but it should not be overly bright. If you allow the visitors to develop night vision early in the tour, they will not need particularly bright lighting. However, in order to allow them to keep their night vision, it is important to shield lights so that they do not get excessive glare from lights (which would interfere with their night vision). Creating overly bright spots and dimmer spots will also interfere with developing night vision. For this reason, using more fixtures with lower wattages is generally more effective than fewer higher wattage lights. Over-lighting the cave can lead to both excessive heat production and algae growth. Furthermore, areas of darkness and shadow contribute to the mystique of the underground experience for the tourists. Marcos Barinas has put a lot of thought into different styles of lighting that will give the tourists some of the same visual experiences that the Indians and the early explorers had with their more limited lighting.

Lighting and Algae Growth

As we noted previously, one of the most significant impacts we can anticipate for development and operation of Cueva de las Maravillas is the potential for development of "lampenflora'. When fixed show lighting is placed in a cave, a variety of plants begin to grow in areas that receive sufficient light. This is especially the case in moist areas. In some cases, the growth of algae is encouraged by additional nutrients that are introduced to the cave through development (lint, etc.). However, sufficient light, moisture and a place to grow (rock or sediment covered surface) are the only factors necessary for growth of these plants. The plants that grow in caves to form lampenflora include cyanobacteria, algae, moss, and ferns. Lampenflora are a significant problem because it 1) detracts from the natural appearance of the cave, 2) could obscure or damage pictographs, 3) could damage speleothems, and 4) could alter the natural food balance for cave organisms. At Cueva de las Maravillas, the potential to obscure or damage pictographs is of special concern.

The severity of the threat to the cave from lampenflora is somewhat difficult to determine; however, it is probably quite high. Most research on lampenflora has been performed in temperate caves. However, the tropical environment seems ideal for more aggressive lampenflora growth than is seen in temperate caves.

Lampenflora are a risk wherever fixed lighting is used in a cave. However, there are numerous ways to reduce the risk of growth. The two variables that are easiest to control are the amount of light and the amount of time the light is on. To reduce the potential for growth, reduce the time the light is on and the amount of light that is falling on moist surfaces. Aley and Aley (1991) reported algae growth on cave surfaces in temperate areas with light intensities as low as 0.8 foot candles. The potential for algae growth is larger in moist alcoves than on convex, flat or dry surfaces. Some types of light promote photosynthesis more efficiently than others and thus lead to more algae growth. For example, most algae and moss is least efficient photosynthetically (and grows most poorly) under yellow light (narrow frequency between approximately 500 and 600 nm). It would be possible to use light of this type in some areas to further reduce the possibility of algae growth in critical areas.

Lampenflora occur in several types of areas. Growth is frequently found near lights, where lights cause bright spots on rocks, sediments, and fixtures near where they are placed. This problem can be reduced or eliminated by careful placement and aiming of lights. Lampenflora can also be found on wider areas that are too brightly lit. As stated previously, lampenflora are best controlled by reducing the brightness and duration of lighting.

Lampenflora can also be controlled by using a sodium hypochlorite(bleach) solution. This is an effective way to control the growth and kill the algae. However, because bleach will also kill a variety of cave invertebrates and natural cave microbes that may be necessary to the natural functioning of the cave, it is important to limit the use of bleach. It should only be applied directly to the smallest area necessary, and it should be used in the smallest amounts necessary. Because of the possible negative effects of sodium hypochlorite, it is better to prevent the growth of lampenflora through careful lighting decisions than it is to treat it after it occurs.

At Cueva de las Maravillas, lampenflora pose a special threat. If it grows in the areas with pictographs, it would be particularly damaging because it could obscure or destroy the pictographs. In addition, any attempt to eliminate the lampenflora with bleach or other techniques could damage the pictographs. For this reason, we recommend careful lighting decisions to significantly reduce the possibility of algae growth in these areas. Some of the options are as follows:

a. Reduce fixed lighting to very low levels and do not direct fixed lighting at any surfaces that contain pictographs.

b. Use only hand-held (non-fixed) light sources for lighting pictographs.

c. Use yellow lighting (potentially gold-sleeved fluorescent bulbs, either with removable or permanent sleeves) in areas with pictographs. This lighting should still be very low intensity; however, the yellow lighting is an additional aid to reducing growth.

d. Keep fixed lighting on surfaces with pictographs below at least 0.8 foot candles, lower if possible.

In case of algal growth on or near pictographs, it will be important to stop the growth quickly. If the growth is not on pictographs, it may be possible to apply bleach to the algae directly with a brush. This would protect the pictograph but would kill the algae. In some cases, it might be possible to kill algae with Germicidal UV lights. These would be used at night to kill algae in areas that could not be treated with bleach. However, these lights are not without their dangers. First, they are hazardous to the operators and should not be used without proper precautions. Second, it is not clear that the pigments of the pictographs are stable under the short-wave UV of a germicidal light. Further research is necessary before attempting the use of germicidal UV lights on pictographs. Again, we must stress that it is better to prevent the growth of lampenflora through lighting decisions than to attempt to remove it. We are currently looking for information concerning these lights and their effect on pigments.

4. Clean-up and Access Control

Unfortunately, Cueva de las Maravillas currently shows the effects of the unrestricted access and visitation that occurred previous to the Ministry's acquisition of the cave. It has a variety of litter and graffiti. This litter and graffiti should be removed to as large a degree possible before opening the cave for tourism. It detracts from the visit and would suggest that these are appropriate in caves. The graffiti removal could begin while development is still proceeding. However, it should not be removed until someone can make sure that no graffiti of historic importance would be removed. A litter clean-up might wait until after development is completed. In particular, some areas that have been covered with dust from construction could be cleaned during the clean-up. It may be possible to get local cavers to help in the clean-ups; however, they should work under the direction of knowledgeable leaders. We are currently collecting information on the specifics of cave clean up that we hope to pass on to you shortly.

The fact that Cueva de las Maravillas has several large entrances in addition to the ones being used for tour operations is a concern in terms of cave protection and security. Unfortunately, the additional entrances are large, complex entrances that would be difficult to gate. In addition, at least some of the entrances are used by bats. It is possible that the bats would be adversely affected by the gating of the entrances. However, it may be possible to fence the dolines that contain the entrances, although fences provide only a degree of security and may still interfere with bats (although to a lesser degree than gates). Onsite security for the cave may be the best option for protection of the cave after it opens and becomes more well-known.

5. Tour and Cave Operations

One of the most important aspects of cave protection for a show cave is the manner in which the tours are conducted. The effective management of people on tours is vital both to the protection of the cave and to facilitating a positive visitor experience in the cave.

One of the most important aspects of people management in cave tours is the size of the tour and the number of guides. We recommend that all tours should be accompanied by two guides. One guide should be at the front of the group and have the primary responsibility for providing interpretation on the tour. The second guide should be at the back of the tour. This guide can assist in overseeing the group to see that no tourists do anything that could damage the cave (leave the trail, touch formations or pictographs, litter, etc.). In addition, the rear guide can also assist in providing interpretation for the people in the rear of the tour. The use of two guides also provides a back-up in case one guide must respond to an injury or other emergency during the tour.

In order for the guides to adequately supervise and inform a tour group, the group must be small enough so that all people can be adequately observed and spoken. This is important not only from a cave protection standpoint, but also from a quality of tour experience. The small tour size is also important from an interpretive standpoint because the size of the tour will allow the guides to make personal contact with each visitor and allow everyone to both see and hear the interpretation. (We have been on a guided tour in Carlsbad that was so large that we were actually in a different passage from the guide who was describing things we could not see, very frustrating). We would recommend that groups be no larger than 20 people (perhaps 15 would be even more appropriate). The small tours will allow the guides to observe the entire tour at all times. In some locations in the cave, the tour will be close to delicate or sensitive cave features (such as pictographs in the passageway). Having guides nearby will discourage people from touching them. If these formations and pictographs are touched they will be permanently ruined. Based on our discussions with Marco and Domingo, we believe that the current tour plans are well in line with our suggestions. We mention this only to reinforce the decisions that have already been made.

Based on observations at a variety of show caves in the United States, we can confidently predict that occasionally there will be people who will get injured, overly tired, afraid, or sick while on tour. For this reason, it is prudent to take a number of steps to prepare for in-cave emergencies. We do not anticipate that emergencies will be a frequent occurrence, but we feel that being prepared for these eventualities is a good idea. Another type of emergency that might be anticipated is a loss of power. Some of the emergency preparedness steps that we would suggest are as follows:

a. Have a wheelchair on site to assist people who become tired or ill. (The wheelchair should be stored in the museum area. That area is climate controlled so the wheelchair will remain in good condition. This area has the added advantage of being close to the cave in case of emergency.)

b. Have a communication system that allows your personnel on park (including in cave) to communicate. This communications system could include radios, telephones, intercoms, a mix of these, or some other system. It is possible that radios could work in the cave, depending on placement of base stations at the entrances being used. Alternatively, a telephone or intercom could be run to selected stations in the cave. These stations would allow guides to get additional help in case of emergencies.

c. Place a limited number of flashlights and first aid supplies in strategic areas of the cave, in case the guides need them in an emergency. These supplies will need to be checked on a regular schedule to be sure that all equipment is in good condition and working order.

d. Drinking water should be available for overheated guests. This can keep a minor problem from becoming a rescue.

Cave operations will require a variety of skilled people at the cave. We feel that the following jobs will be important. Some jobs might be combined, but others will require specialists.

Cave Employees:

1. General Employees:

Security: night watchmen

Cashiers for entrance and gift shop

Outside of cave and museum clean-up

Ticket takers

Local park administration

2. Cave Unit

Guides

Nightly and periodic in-cave clean-up

Electricians and Maintence - 2 types:

1) those who are on-site constantly that can deal with minor repairs to the lights

2) another group on call to deal with major repairs and changes to the system.

Professionals to monitor changes in the cave (can be offsite consultants to some extent, but having one onsite person helping run the cave operations would be useful)

We have a few additional suggestions that may ease cave operations.

We suggest use of a three-part ticket at the site. The ticket would be sold at the ticket stand. When people enter the restricted area, the first part is removed. The second part is removed by the guide when he/she assembles their tour. The third part is a souvenir for the visitor.

In the gift shop, be sure to provide some very inexpensive items that children can purchase.

Provide a significant number of umbrellas at the exit to the museum for guests to use on rainy days to get from the museum to the cave entrance.

Provide trash cans at strategic spots outside the cave, especially where the guides will be talking about cave conservation. Remind people to discard trash, cigarette butts, chewing gum etc. before they enter the cave.

Plan for protection of the major electronic and mechanical systems when hurricanes hit the area.

6. Resources Inventory and Cave Condition Monitoring

In order to adequately protect the cave, it is important to monitor the condition of the cave to identify changes before they can cause irreversible damage. It is also important to monitor conditions to demonstrate a commitment to protection of the cave to critics of the project. In the case of Cueva de las Maravillas, we feel that several types of monitoring are important. We recommend the following monitoring programs as minimal. Furthermore, we encourage development of additional inventorying and monitoring programs to better understand and protect the cave. These programs can contribute significantly to the knowledge of the cave and to interpretive programs. Overall, we feel that photomonitoring, basic cave climate monitoring, and monitoring of the bat populations are necessary.

Photomonitoring will be particularly important in the case of Cueva de las Maravillas. During our visit, we observed a major effort to photodocument the pictographs in the cave. Ongoing photomonitoring is a set program of photos taken at designated intervals to identify changes that have occurred. In order to be maximally useful, photos must be repeated as exactly as possible. They must be the same views taken with the same camera conditions and lighting. Duplicating the conditions for the photographs as closely as possible is important to be sure that changes identified in the photos are due to changes in cave conditions rather than photographic parameters. This effort can serve as an important baseline for identifying any potential changes that occur and serve as a signal that the resources need additional protection.

In addition, monitoring basic cave climate variables is vital. In particular, it is very important to monitor cave temperature and humidity in a number of places in the cave. There are two potential ways to accomplish this monitoring (manually and with automatic data loggers). It is possible that a mixture of these means would give the best results. It is necessary to designate a set of points for environmental monitoring. At each of these places, temperature and humidity would be read (either manually or with data loggers) at set intervals. In addition, monitoring evaporation or condensation rates would be appropriate (as a check on moisture changes in the cave). Evaporation is probably best monitored manually on a weekly or monthly basis. A variety of data loggers are available for measuring the temperature (and to a lesser extent humidity). Some of the best and easiest to use are HOBO series loggers by Onset Computer (for more information see http://www.onsetcomputer.com/). Another (cheaper) option for temperature are Thermochron iButtons by Dallas Semiconductor http://www.ibutton.com/ibuttons/thermochron.html). The Thermochron iButtons do not have the resolution of the HOBO loggers. We would recommend a few HOBO loggers for permanent stations and some iButtons for additional sites. One additional variable that should probably be monitored is carbon dioxide level. CO2 levels may be altered by tour operations, and changes in CO2 levels may impact pictographs or cave formations. Monitoring CO2 levels can be done manually using Draeger tubes or other methods used in various industries. We feel that environmental monitoring should begin as soon as possible. This would provide a baseline of data gathered pre-opening with which to compare after daily tours begin in the cave.

We would also recommend placing a basic surface weather station on the park outside the cave. Having a surface weather station will allow you to correlate changes in the cave environment with changes in the surface weather. Being able to make these comparisons is important so that you can separate cave environment changes that are the result of weather changes from those that are the result of tour activities.

We feel that it is important to monitor the bat populations using the cave to assure that tour operations are not negatively impacting the differing bat populations. This monitoring will be quite elaborate because of the nature of the populations and the complex nature of the cave. We recommend that appropriate people with experience in monitoring tropical bat populations be contacted for assistance in developing a monitoring plan. You may be able to set up a program with a university in the United States or Latin America that would benefit from the ability to do scientific research in the cave and provide you a valuable service for the privilege of working there.

There are several other aspects of the cave that may need to be evaluated; however, some of them may already have been addressed. The invertebrate biology of the cave is potentially very interesting. If it has not been studied by a cave biologist, it should be. The excavations in the bat roost area indicate that the cave has interesting paleontological potential as well. The results of those excavations should be examined to determine their significance. According to Keith Christenson, some of the paleontological findings have been published in the Boletin del Museo del Hombre Dominicano. Because Domingo Abreau is intricately involved in the project, we presume that the archaeological potential of the cave has been evaluated.

7. Museum Operations

We feel that developing the site museum in the small cave above the main portion of Cueva de las Maravillas is one of the most unique and exciting portion of the project. Nevertheless, in developing the museum in the small cave, it is vitally important to remember that, although the museum may be somewhat climate controlled, it should not be developed as an indoor space. It is enclosed, but it will have many characteristics of an outside space. The display materials as well as the fixtures and lighting will need to stand up to variable environmental conditions, especially humidity.

An air-curtain entrance to the museum, as opposed to a door, may be of some advantage to cave conservation, as well as be easier to construct because it would remove some of the lint and dust from people's clothes before they enter the museum and cave.

Presentation in the museum:

Geology:

There should be some display which explains how this particular cave was formed in addition to a general description of how and where caves generally form. Some information should be provided on the different types of caves that are found in the world and the Dominican Republic as well. Pictures could be included from some of the different types. (Though not showing pictures from any caves you are trying to protect in the DR). If this display could be situated in the section of the museum where the coral happens to be found on the wall, it would be particularly special in that it would be a real example as opposed to a constructed one.

The large stalagmite in the middle of the trail in the big room that needs to be removed could be cut in half vertically and polished to show how stalagmites develop.

Biology:

Include information and pictures of the different species of bats that are living in the cave. Be sure to include information about how bats are beneficial to the environment (that they eat harmful insects and that they pollinate plants and distribute seeds etc.). If there is any information about how the Taino Indians viewed bats, that would be interesting to include as well.

Discuss other life in the cave, the insects (beetles, crickets, spiders, etc.). Try to show in some way the interconnectedness of all the species in the cave, how they all live off of each other. You might also deal not just with life in the depths of the cave, but entrance life as well. What types of animals

and insects dwell in the entrance areas? How do they use the cave? Historically, were there other species that were using the caves which are no longer present in the Dominican Republic?

Anthropology:

Create a diorama that shows Taino people doing what they did in the cave. This could be people making pictographs such as will be seen on the tour. Describe how the Taino are thought to have viewed caves and how they used different areas of the cave. You may also want to discuss how use of the cave changed over time. You could also report on findings of archaeological/paleontological/historical studies that have been done to show the significance of this cave to the scientific world.

Conservation Area:

Be sure to include a section in the museum that details what measures you have gone to in order to protect the cave (good promotion for the government and its efforts). Also, discuss cave conservation: the effect of touching the formations, graffiti clean-up, protecting the bats, etc.

This report may not fully cover each of the issues that we have addressed. Please feel free to contact us if you have further questions. We found working on this project a great pleasure and would be happy to assist further on this or future projects.

Support for this report came primarily from the Ministry of Environment of the Dominican Republic. Additional support to Dr. Toomey came from the State of Arizona which contributed his salary as a governmental exchange.

About the Authors

Rickard S. Toomey, III, has a B.S. in Geological Sciences from Brown University (1985) and a Ph.D. in Geological Sciences from The University of Texas at Austin (1993). His dissertation is entitled Late Pleistocene and Holocene Faunal and Environmental Changes at Hall's Cave, Kerr County, Texas. From 1994 to early 2001 he was at the Illinois State Museum, first as a post-doc, then as a technology and education specialist and finally as an Assistant Curator of Geology. He has worked extensively on cave paleontology. This includes an on-going study of the paleontology of caves at Mammoth Cave National Park. The work at Mammoth Cave has included work on reconstructing cave environments and restoring habitat for endangered bats. Rick has worked on the Illinois Department of Natural Resources’ Karst Working Group in developing management policies and protection strategies for caves and karst. Rick has been President of the Illinois Speleological Survey and National Speleological Society, Paleontology Section. He is the president of the Cave Research Foundation.. In April 2001 he became Arizona State Parks’ Cave Resources Manager.

Elizabeth Grace Winkler began working in caves in 1991 in Nuevo Leon, Mexico. In 1993, she became a member of the Cave Research Foundation, a non-profit group dedicated to the scientific study, exploration, and mapping of caves. She has been involved primarily in the Mammoth Cave National Park Project although she has also been involved in mapping projects in Indiana, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama. Currently, she serves as the Administrative Director of the Hamilton Valley Research Center. From 1982 to 1986, she was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Dajabon, R.D. working in agroforestry and rural development.